BY TOBIN LEVY

“Most boys here are as much a cowboy as a woodpecker is a carpenter,” says a man named Ed, surveying the scene at downtown’s historic Saengerrunde Hall.

It was the night of the annual Spring Fling, a private party crowded with fixtures in Austin’s two-stepping and swing-dancing community. (The event is so popular that its sister event, the Fall Ball on Nov. 17, has long been sold out.)

Ed, in his early 60s, speaks with a deep Texas twang. Bearded, burly and sporting a Stetson, Ed warranted the cowboy title, as did another man nearby wearing starched Wranglers, drinking hooch from a water bottle and using a portable fan that runs on a power-drill battery. This was not his or Ed’s first rodeo.

Everyone in the dance hall deftly glided across the floor. To those who follow musicians like Dale Watson and Jesse Dayton, the two-steppers were familiar faces — the same men and women whom amateurs gawk at from bar stools while swearing to themselves they’ll sign up for private lessons the next day. Tonight, the dancers seemed grateful to be unencumbered by tyros, who inadvertently elbow their neighbors, trip over themselves and go backward when they’re supposed to go forward at the Broken Spoke.

But most of the dancers at Spring Fling weren’t cowboys or country-livin.’ Ed wasn’t as much judging as he was eloquently making an observation.

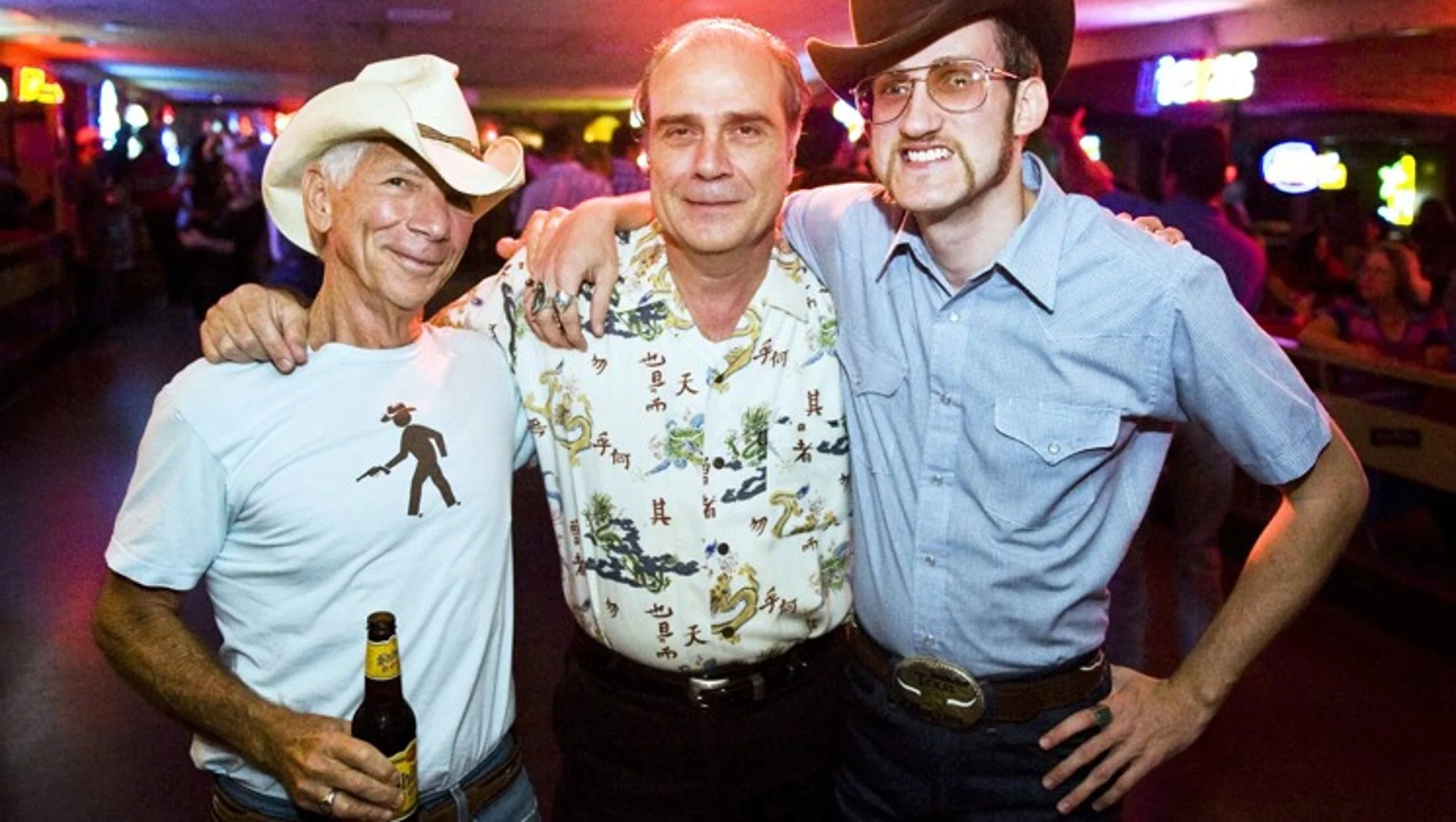

Three of the men on the dance floor – the smooth Larry Vanston, the kinetic Hunter Magness and the polished Joel Gammage — are all known throughout the two-stepping community. Women of all ages, shapes and sizes ask them to dance as if it were Sadie Hawkins day, every day.

Yet, the men’s shared pastime seems out of sync with their respective demeanors. And when it comes to how and why they dance and what they do when it’s light outside, these men are as different from one another as their sartorial preferences suggest.

The suavest dancer in town

In terms of his dancing style, Larry Vanston is more Fred Astaire than he is Bud Davis from “Urban Cowboy.” He’s perhaps the suavest dancer in town.

Vanston is also a prime example of one of Austin’s many two-stepping mavens whose wardrobe alludes to a day job that has nothing to do with horse wrangling. Vanston’s usual, often monochromatic dance attire is a short-sleeve collared shirt, pressed khaki slacks and Italian loafers. (He often goes out directly from work.)

At Spring Fling, the 57-year-old engineer looked dapper in a handsome suit and fedora. There’s a formality to his wardrobe that mirrors his formal, almost wistful dancing technique.

When dancing, Vanston appears to be deep in a moony reverie as he moves across the floor. His face, like his prominent eyebrows, is always tilted slightly up. He’s always grinning at his partner. Yet he rarely speaks.

“I’m not a talker; I’m a listener,” he explains. Vanston’s silence makes an abstract kind of sense. His dancing style is a complex amalgam of eras – Lindy Hop, jitterbug, polka and Western swing – some of which, at least cinematically, were silent ones. Unlike traditional two-steppers, rather than maintaining a rigid frame, he dances into the ground, with his hips, knees and feet in constant motion.

Vanston became a regular on Austin’s dance scene in the late ’90s when, after 15 years of marriage, his wife called it quits. He was a single dad of three — a 5- and 10- and 14-year-old – all of whom unexpectedly moved in with him. At the time, Vanston was working 40 to 60 hours a week at his father’s engineering firm, Technology Futures, which specializes in telecommunication systems. (Vanston is now president.) He’d come home from work, cook dinner, put the kids to bed, wake them up in the morning and repeat.

“I spent the first couple of months getting organized, and then I decided that I needed a hobby.” Late nights aren’t exactly conducive to child rearing and a demanding job. “I learned to get by with five hours of sleep,” he says. “As time has gone on, that’s become more of an issue.”

Vanston’s hobby of choice wasn’t exactly random. He enjoyed a formal dance class at the University of Texas, where he earned his Ph.D. He spent time at the Broken Spoke when he was in his early 20s. And he and his ex used to go dancing from time to time. But Vanston was relatively new to Western swing, so he signed up for private lessons at Four on the Floor dance studio. Fortuitously, his instructor was a fellow engineer.

“She was able to break everything down into steps that I could understand,” he says. This meant explaining swing using abstruse (if you’re not an engineer) concepts, like the four-bar mechanism. “It’s all a study of kinematics in engineering, predicting what the acceleration, direction and velocity of every point on every bar is.”

According to Vanston, smooth transitions require an acute awareness of the rate of change in velocity. “Now, the derivative in the change of your acceleration is called jerk, and that’s when you are accelerating and all of a sudden decelerate.” This leads to wrenches and tugs and internal monologues like please, Lord, let this song end. “Jerk is an engineering term. And if you get jerk in an engineering system, that causes stress, and things break.”

In the 1990s, Austin was in the midst of a swing craze. “Those were the golden years,” says Vanston, citing bands like 81/2 Souvenirs, the Jive Bombers, the Day Jobs, Merchants of Venus and the Lucky Strikes. In the early 2000s, dancing trended away from swing and toward country, yet the crowd stayed mostly the same.

Today, the community generally revolves around bands and musicians like Dale Watson, Heybale, Two Hoots and a Holler, Chaparral and Jesse Dayton, among others. Like most dancers, Vanston follows the music rather than the venues, though most of the bands he mentions play at the same places: the Continental Club, Broken Spoke, Ginny’s Little Longhorn, the Highball, the White Horse.

When asked about the anarchy that is dancing at the White Horse, which is still relatively new and often filled with amateurs, he says, “It’s really fun to see the hipsters dancing, and to see some of them get good at it. And I’d never have predicted 20 years ago that I’d be dancing to Prince’s ‘Purple Rain.’ ” (One of the bands plays a blues version of the song.)

Vanston, who recently became an empty-nester, usually travels solo on his nights out, which are most nights. It lends itself to an array of partners and a multitude of safe non-relationships. “In a marriage you’re always in the doghouse if you do something or you don’t do something,” he explains. “The longer it goes on, the more of a chore it becomes. On the dance floor, if you’re a good dancer like I am, and very attentive like I am, for three or four minutes I can pull it off and keep a smile on your face. That’s pretty wonderful. Then, just before you’re fed up with me, I can go on to the next girl.”

Epitome of ebullience

“Larry and I have two totally different styles. And he is a much better dancer than I am,” says Hunter Magness, who’s out and about three or four times a week. “There are a lot of guys out there who can dance a lot better than I can, but there are very few who have as much fun as I do.”

At the Spring Fling, Magness for once traded in his customary garb – a T-shirt, cut-offs, and red high-top Converse – for jeans and a casual long-sleeve button-up. When dancing, the 65-year-old looks more like a sprightly rogue than a retired Houston police officer. He’s known for leaping up as if performing a quadruple under in a game of jump rope. He’s often referred to as “the hopper.”

On and off the dance floor, Magness is the epitome of ebullience. A character sketch of him necessitates buoyant adjectives and hyperactive verbs. There’s a skip to his walk. For exercise, he athletically bounds around Lady Bird Lake. Though he’s capable of the “Quick Quick Slow Slow” two-step (the title of Dale Watson’s song/tutorial for beginners), Hunter prefers the “quick quick.”

When dancing, he sporadically jumps, makes jazz hands, offers a high-five (actually a high-ten) to his partner, gives her a subtle hip chuck, and often positions himself so that he’s briefly standing back to back with whichever woman who’s asked him to dance. She’s almost always smiling, having embraced the capriciousness, improvisation and unapologetic rule-breaking that is dancing with Magness.

For him, part of the joy of dancing is reminding his partners that there are no wrong moves, there’s never a reason to apologize for missing a beat, and that the priority is having a good time.

“You really don’t have to know how to dance as long as you think you know how to dance,” he says. “Eye contact and a smile go a long way in getting people to dance with you. Like the old saying goes, girls just want to have fun. They don’t want to dance with some guy who looks half dead or constipated.”

Magness may qualify for Social Security, but on the dance floor he’s more animated than most 20-somethings and far less self-conscious about what he’s wearing. “I like dancing in silly things,” Magness says, and lately that often means flip-flops. His fashion sense is as unique as his dancing style. “When I dance, the music makes me jump. I will jump four feet in the air. I am more of a wild child.”

It’s easy to imagine what he was like as a child. “I used to jump out of trees and off the porch and bust myself up,” he recalls. “My mother had to keep me on a leash or I was gone.”

Magness, whose father was a colonel in the Air Force, was raised all over the world. He graduated from high school in California and then moved to Austin with his family when his father retired from the military and went to work for the University of Texas. Magness also joined the Air Force and spent four years at Lackland Air Force base in San Antonio. In 1969, the day he completed his service, while heading to Austin, listening to Janis Joplin in his ’67 Chevelle Super Sport, he made an impromptu stop at Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos. “I knew I could go to college on the G.I. Bill. So I went into the school and, let me tell you something, there was nothing but girls. I thought, oh my God, I want to go to school here.” And he did.

After graduation, Magness moved to Houston. For five years, he worked as a state trooper and then enrolled in the police academy. For the next 20 years, he worked street patrol in Houston. “I was promoted to sergeant and became a street supervisor. I also did some investigating work, which I did not like at all. It was boring, just paperwork.” he says. “The real police work is the guys in the car. They are the first ones to the murders and all of the crimes.”

Though it’s a dangerous job, “I never really got hurt,” he says. “You know, just beat up and stuff like that. Or thrown down some stairs. Hit on the head.” Magness retired in 1996. “I was so jaded and cynical for a long time after that. It’s the kind of job that makes you rigid, and you develop a hard attitude. You see such horrible things happening to decent people.” After retirement, he got a divorce, moved to Austin and took up dancing. “I wasn’t in a very good mood,” he says, which is almost as hard to envision as him in a uniform.

“When I first started, I wanted to forget about parts of my past, and dancing helped, but now I just do it for the fun,” says Magness, who has two grown daughters. “There isn’t anything I really want to forget, because I am pretty happy with what’s going on with my life. But dancing is like a catharsis. While you are dancing, you tend to forget, and that’s why I think a lot of people dance. You know, to forget about their jobs, relationships, life and even health issues. I know a lot of people who dance just for that reason.”

When Magness isn’t hopping to music, he’s at his little ranch outside town, fishing on the lake. “Sport fishing is my first love,” he says. And, on his left calf, he’s got the tattoos to prove it. There’s a rainbow trout, a speckled sea trout, and a largemouth black bass – all of which you catch sight of when he’s on the dance floor, wearing shorts and jumping straight up in the air.

The Texas Hatter

At only 25, Austin native Joel Gammage inspires awe and envy on the dance floor. He’s mastered the traditional Texas two-step and Western swing. His style is about form, posture and perfection. Gammage is one of the exceptions to Ed’s statement of almost truth at the Spring Fling.

Though Gammage doesn’t spend his days on a ranch, he makes cowboy hats for many people who do. When out on the town, he almost exclusively wears boots, jeans, and a button-up that’s been neatly tucked behind a belt and a conspicuous buckle. And he’s always wearing a 1940s or ’50s-style cowboy hat of his own making. Yes, he’s related to the Manny Gammage, the late, longtime proprietor of Texas Hatters and a local celebrity.

Texas Hatters is a family-owned and operated business that’s been making custom hats for 85 years, a birthday Gammage is celebrating Oct. 13 with “Manny Gammage’s 85 Years of ‘Topping the Best’” party — a free, daylong event in Lockhart (where Texas Hatters is now located) with an impressive roster of bands and sponsors. Gammage, Manny’s grandson, has successfully carried on the millinery tradition; however, he’s also made a name for himself as a club and band promoter, the founder of the Texas Hatter Music Series in Lockhart, and as one of the best Texas two-steppers in Austin.

“If you want somebody to give you a whole different set of insights, it would be Joel Gammage,” says Vanston. “He’s picked up all of the traditions and is a fantastic dancer.”

Gammage is soft-spoken, prefers words like “gosh” over expletives, opens car doors for women and, because he doesn’t drink, often assumes the role of designated driver. He’s beanpole thin, boyishly kind and earnestly respectful — the type of guy people trust with their house keys and really nice cars.

Though he stands 6-foot-3 without a hat, he almost always wears one when dancing. For spectators, the fact that he towers over most of his partners is an afterthought. He simply guides from above, and his partners’ spins seem smoother for it. Even the least confident women are comfortable following the silent direction.

One first-timer called Gammage the puppet master, “though in a good way,” he says. When a move requires Gammage to take off his hat mid-dance, the removal and return appear a natural, almost involuntary gesture, probably because he’s been dancing his whole life. “Technically, before I was born,” he says. “When my mother was pregnant with me, she went dancing at the Broken Spoke. It’s where my roost is.”

When Gammage was a child, he and his family were regulars at the Spoke, which used to be down the road from Texas Hatters. They have a long-standing relationship with James White, the owner. Manny Gammage made custom hats for White and for many of the musicians who played at his bar, including Willie Nelson, Jerry Jeff Walker and Don Walser. Manny also sold hats to the patrons.

Gammage worked alongside his grandfather until Manny died in 1995. As soon as Gammage was old enough to drive, he was at the Broken Spoke, a fourth-generation Texas Hatter, carrying on his family tradition.

“The funny thing is that when I originally went there, I went there to sell hats,” he says. “So I would sit in the bar with James White and his family. All the old cowboys would be sitting around the bar drinking and talking, and I would talk to them about my grandfather and the hat shop and let people know we were still in business.”

White took Gammage under his wing. “If there was somebody that he thought I should know, he would introduce me to them, and I would end up selling them a hat. If there was a tour bus of girls, he would grab me by the arm, take me over and introduce me, then get me to dance with them.”

When he’s dancing, it’s not unusual for someone to buy a hat right off his head or order one from him in between songs. “Dancing for me is my hat business. The majority of the people that I sell to are in the dance community or are musicians.” He jokingly refers to himself as the “dancing salesman.” “I usually keep a tape measure with me. I usually have it hanging out of my back pocket.”

Gammage is recognized not only as a hatter but also as a designer, with each hat being different than the next. “They just pay me, and I make whatever I want to make them. It’s pretty unique. It’s like talking to an artist; if you are going to pay an artist, you wouldn’t tell them what paint. You would just let them paint it.”

Like Vanston and Magness, Gammage tends to follow the bands rather than the venues, and he’s somewhat ritualistic about where and when he goes out, particularly now that he’s moved to Lockhart. It’s usually Ginny’s on Sunday afternoon, Heybale at the Continental on Sunday night. Thursdays he first goes to the Spoke for Jesse Dayton, then to White Horse for Mike and the Moon Pies. Depending on the band, he’ll often stop by the Spoke on Friday and Saturday. Sometimes, when the bars close, he’ll go to breakfast. It doesn’t leave much time for sleep.

“I don’t get many hours of sleep a night, maybe four hours,” he admits. “I’ve just got so many different things that I want to do today. Dancing is like my way of actually sleeping. I just zone out when I’m dancing from song to song, until it all just runs together.”

Gammage’s dance card is always full. “I get a lot of women that will come up and ask me to dance. See, it makes me blush!” he says, and his face does, in fact, turn crimson. “I will have 10 women in a row come up as soon as the band stops.” He is the perfect gentlemen when it comes to rectifying the situation. “I remember in which order they asked me to dance, then the next time the band stops, if another person asks me to dance I will not dance with her until I’ve danced with the other girls in the order in which they asked.”

For Gammage, the dancing community is an extended family. “You can go out five nights a week and see the same 30 to 50 people. It’s weird,” he says, “they are bar room people, but they’re not a bar room crowd. Half the time they aren’t even drinking because they love dancing too much. Sometimes I get a weird backhanded compliment, where somebody says, wow, you’re so responsible even though you grew up in a dance all with all these drunks. It wasn’t like that. The dance community doesn’t really drink, or rather, it’s all within limits.

“And I grew up around Larry, who is a software guy, and Hunter, who retired after 20 years in the police force. Another dancing friend of mine is a Republican lobbyist; another works with the Texas Association of Business.” He lists an array of people whose day jobs seem incongruous with two-stepping, particularly on a weeknight. The community is not exclusive, but it’s not exactly inclusive either.

“It’s open (to new people) and it’s not open. Like the Fall Ball and the Spring Fling, there is a boundary to it. You can’t just buy tickets. You have to be a sponsor. Because sponsors only get eight tickets, you have to be selective about who you give them to. Those events are about the core groups of dancers; it’s like a big family reunion.”